Only 1 week left to get the Kindle and kobo versions of The Summer Before the Storm at the special price of only $2.99! Visit this website for links to the e-books.

In remembrance of The Great War during this centenary year, this blog will explore the intriguing social history of that tumultuous time. The first two of my Muskoka Novels – "The Summer Before the Storm" and "Elusive Dawn" – take place from 1914-1918. During my four years of research I accumulated a trunkful of notes, and will illuminate some of the more interesting and unusual tidbits, beginning with the Age of Elegance.

Wednesday, July 30, 2014

Wednesday, July 23, 2014

Shell-Shock

They trembled, couldn’t sleep, were terrified of loud

noises, suffered from headaches, dizziness, ringing in their ears. Some lost

their memory or the ability to walk or talk. But they were often considered

cowards or malingerers. One doctor said that shell-shock was a

"manifestation of childishness and femininity". Treatment included

electro-shock therapy, hot and cold baths, massage, daily marches, athletic

activities, and hypnosis.

Officers were sometimes given psychoanalysis as well,

especially at the famous Craiglockhart War Hospital in Scotland, which treated

poets Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen. Read Sassoon's poem "Survivors", about

shell-shocked soldiers, which he wrote while he was there.

Shell-shocked officers were said to have neurasthenia while

the men (usually from the "lower classes") were classified as

hysterics.

Medical evidence showed that shell concussion could cause

neurological damage - tiny hemorrhages in the brain and central nervous system.

But men exhibited symptoms of shell-shock even when they had not been exposed

to artillery fire. In 1916, a distinction was made between those who were

shell-shock wounded (W) and sick (S). Wounded was honourable, and entitled the

victim to wear a “wound stripe”. The

others received no stripe or even pension.

In 1917, the term shell-shock was no longer allowed. Patients

were classified as Not Yet Diagnosed Nervous (NYDN). The men called it Not Yet

Dead Nearly. It’s now referred to as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

Understandably, many of my characters suffer some degree of shell-shock.

Tuesday, July 22, 2014

Special Promotion on E-books!

"It was the whisper that started their war. That's how

many at the table that evening would recall the summer of 1914."

So begins The Summer Before the Storm, the first of the

Muskoka Novels. Since it's two weeks until the 100th anniversary of Canada

going to war, there's a special price for the Kindle and kobo versions of The

Summer Before the Storm. Only $2.99! Don't miss out on this limited-time offer,

which ends Aug. 5. Visit this website for links to the e-books.

Wednesday, July 16, 2014

Sex and the Soldier

|

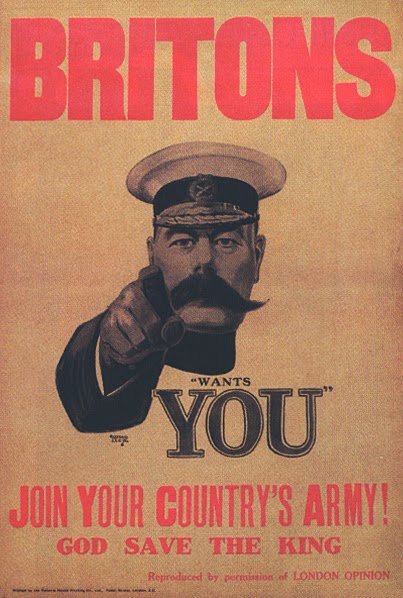

| Lord Kitchener recruiting poster |

Lord Kitchener wanted men to enlist, but he also advised

them, "In this new experience you may find temptations both in wine and

women. You must entirely resist both temptations, and, while treating all women

with perfect courtesy, you should avoid any intimacy.”

But as Robert Graves wrote in his classic memoir, Goodbye

to All That, "There were no restraints in France; these boys had

money to spend and knew that they stood a good chance of being killed within a

few weeks anyhow. They did not want to die virgins.”

|

| Talbot Papineau |

Canada and Britain’s top Ace, Billy Bishop, disclosed his

affair with a French girl to his fiancé before their marriage in 1917. In Tapestry

of War, Sandra Gywn explores Major Talbot Papineau’s correspondence

with a close female friend. “In a manner that for the time was uncommonly

frank, he’d confessed much about his sexual transgressions in London.” Papineau was killed at Passchendaele in 1917.

What is surprising is that the military sanctioned visits to

licenced brothels, as sex was considered a physical necessity for the men. The

"maisons de tolérance" with blue lamps were for officers, and red

lamps, for the other ranks. However, no sex education or prophylactics were

provided. An astonishing 400,000 cases of venereal disease (VD) were treated

during the war, according to the BBC.

The rate of VD among

the Canadian troops was almost 6 times higher than that of the British, and was

1 in every 9 men. Not only were the Canadians far from the influence and

advantages of home, but their pay was also 5 times that of their British counterparts,

so they had ample funds to buy sex and wine.

Troops who ended up in specialized VD hospitals were docked

their pay, while officers had to pay 2 shilling and 6 pence for every day they

spent in a VD hospital, and also lost their field allowance. Soldiers with VD

were not eligible for leave for 12 months. But contracting VD was also a way to

escape the horrors of the trenches, at least for a while.

My first two Muskoka Novels, The Summer Before the Storm

and Elusive

Dawn, explore the theme of wartime morality.

Labels:

1914-1918,

Billy Bishop,

brothels,

Canadian history,

historical fiction,

history,

Lord Kitchener,

Muskoka Novels,

Robert Graves,

Sandra Gwyn,

social history,

Talbot Papineau,

The Great War,

VD,

WW1,

WW1 sex

Wednesday, July 9, 2014

Hospitals Flapping in the Wind

|

| #2 Canadian General Hospital in Le Tréport, France - Collections Canada |

Many of the military hospitals in France and Belgium,

including those well behind the lines on the French coast, housed the wounded

(and staff) in tents. The winters of 1916-17 and 1917-18 were brutal - among the coldest

in living memory - which made life miserable as well as difficult for staff and

patients alike. These tents were occasionally blown down in storms, which were

all too frequent on that windy north coast. Three hospitals were virtually levelled in a gale in August, 1917.

Some of these tented and hutted hospitals had 2000 or more

beds, and with the additional accommodations and facilities required for medical and

support staff, were like small towns.

During an offensive, a hospital like the 1st Canadian

General at Etaples could have 600 admissions a day. In 1917, that hospital

alone admitted 40,500 wounded and ill men. It's delightful to see that there was still time and care taken to bandage a dog's paw, as seen in the photo above.

|

| The largest CWGC cemetery in France, at Etaples, with 11,000 WW1 graves - photo copyright Melanie Wills |

Although seemingly well behind the front lines, the base

hospitals were occasionally hit in bombing raids. During one on May 19, 1918, over

60 staff and patients were killed and 80 wounded at the 1st Canadian General,

while there were another 250 casualties among the other hospitals in the

Etaples district. Contrary to the Geneva Convention, these hospitals had been

placed next to vital military installations that were legitimate targets for

the German bombers. The middle and right graves at the front of this photo are those of a Canadian doctor and nurse killed in that attack.

Some of my characters work in these hospitals in Elusive Dawn.

Wednesday, July 2, 2014

The Art of War

My characters enjoy spending time with real people, so it’s

understandable that ambitious Jack Wyndham is thrilled to meet powerful ex-pat

Canadian millionaire, British MP, and newspaper baron, Sir Max Aitken, who

becomes Lord Beaverbrook in 1916. A self-made man, Aitken admires Jack’s

cleverness and business savvy, but also recognizes his artistic talents, and

hires him to be one his war artists.

|

| "A Copse, Evening" by A.Y. Jackson. Beaverbrook Collection of War Art, Canadian War Museum |

Farsighted and always a staunch Canadian, Aitken established

and financed the Canadian War Records Office in 1916 in order to document Canada’s

war efforts in film and photographs, despite initial opposition from the War Office.

Troops and other personnel, like nurses, were not allowed to have cameras

overseas, so these official photographers produced vital historical records.

|

| "War in the Air" by C.R.W. Nevinson, Beaverbrook Collection of War Art, Canadian War Museum |

Beaverbrook also established the Canadian War Memorials

Fund, hiring artists to capture Canadians on the home front – in the fields and

factories – as well as in the trenches. Nearly 1000 paintings were created by

artists such as A.Y. Jackson, Frederick Varley, and Arthur Lismer, who would

later become members of the Group of Seven. The “War in the Air” painting above depicts Canada’s and Britain’s

top Ace, Billy Bishop, in combat.

After decades of lying sadly neglected and unseen in the vaults of the National Art Gallery, these treasures are now housed at the Canadian War Museum, where some are on permanent display.

After decades of lying sadly neglected and unseen in the vaults of the National Art Gallery, these treasures are now housed at the Canadian War Museum, where some are on permanent display.

In Elusive Dawn you can join Jack

Wyndham for a country house weekend at Max Aitken’s estate, Cherkely Court.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)